Both these complaints were rejected.

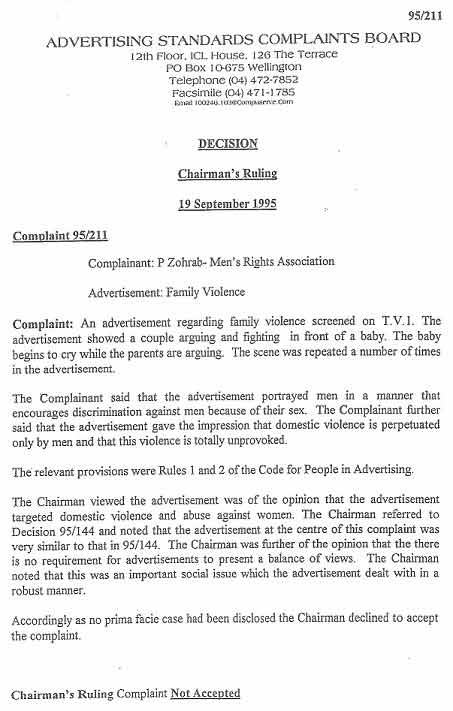

On the issue of incompetence, I wish to point out that the Chairman's

Ruling on my complaint (Decision 95/211) stated that the advertisement

which I was complaining about was "very similar" to the

advertisement which was the subject of the complaint in Decision 95/144.

This was one of a mere four points which the Chairman used to support

his ruling, but this point is at best irrelevant. I was complaining

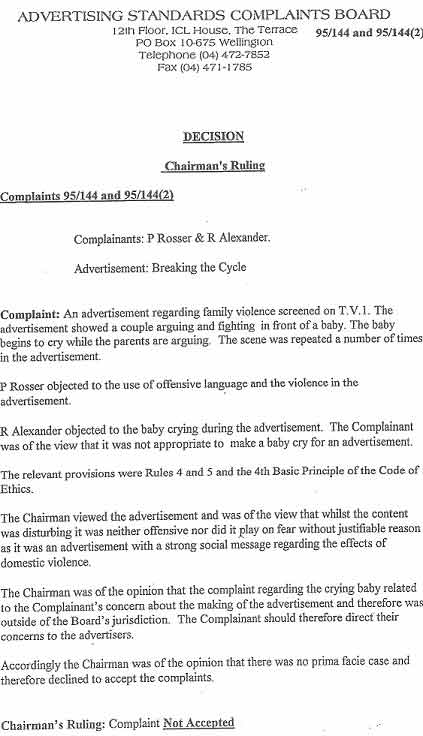

about discrimination against men, whereas the complainants in Decision

95/144 were complaining about offensive language, violence and causing

a baby to cry in order to make an advertisement. The points at issue

were therefore totally distinct, and the fact that the advertisement

was on a similar topic in the two cases was purely fortuitous. This

is incompetent.

On the issue of bias, I wish to point out that the Code for People

in Advertising http://www.asa.co.nz/code_people.php

lists the following relevant principles:

-

Advertisements should comply with the laws of New Zealand. Attention

is drawn to the Human Rights Act 1993 and the New Zealand Bill of

Rights Act 1990.

-

Advertisements should not portray people in a manner which is

reasonably likely to cause serious or widespread hostility, contempt,

abuse or ridicule.

-

Advertisements should not portray people in a manner which, taking

into account generally prevailing community standards, is reasonably

likely to cause serious or widespread offence on the grounds of

their gender; race; colour; ethnic or national origin; age; cultural,

religious, political or ethical belief; sexual orientation; marital

status; family status; education; disability; occupational or employment

status.

-

Stereotypes may be used to simplify the process of communication

in relation to both the product offered and the intended consumer.

However, advertisements should not use stereotypes in the portrayal

of the role, character and behaviour of groups of people in society

which, taking into account generally prevailing community standards,

is reasonably likely to cause serious or widespread offence, hostility,

contempt, abuse or ridicule.

These principles respectively proscribe discrimination against men,

the portrayal of men in a manner which is reasonably likely to cause

serious or widespread hostility, contempt, abuse or ridicule, the

portrayal of men in a manner which, taking into account generally

prevailing community standards, is reasonably likely to cause serious

or widespread offence on the grounds of their gender, and the use

of stereotypes in the portrayal of the role, character and behaviour

of men which, taking into account generally prevailing community standards,

is reasonably likely to cause serious or widespread offence, hostility,

contempt, abuse or ridicule.

However, these principles were completely ignored by the Advertising

Standards Complaints Board. At most, it could have wriggled out of

a positive decision on the complaint by claiming that, taking into

account generally prevailing community standards, such negative attitudes

and actions towards men are so common that this advertisement could

not have been expected to change society's attitudes one iota!

However, the Chairman's Ruling did not mention any of the above

principles at all. The Chairman noted that "there is no requirement

for advertisements to present a balance of views." However, there

were no views expressed in the advertisement whatsoever, so this remark

was completely irrelevant, and was targeted at excusing discrimination

against men. The Chairman also noted that "the advertisement

targeted domestic violence and abuse against women." However,

the very point of my complaint was that targeting "abuse against

women" was discriminatory against men, since what should have

been targeted was domestic violence, no matter who the victims and

perpetrators were. Far from fighting discrimination the Chairman

in fact practised discrimination in this ruling.

I do not expect that the Law Commission will accept my argument

here, because I have had many years' experience of the Law Commission,

and I do not believe that they have any concept of men having any

rights – any more than the Advertising Standards Complaints

Board does. The Law Commission made a huge song and dance about women's

access to legal services , some years ago, but failed to unearth

any issues which were even remotely as serious as the fact that there

is an offence called "Male Assaults Female"

(which the Law Commission has referred to very discreetly in some

proposals on the Crimes Act in general) and the fact proven by Justice

Ministry research that

men get more severe sentences for the same crime than women do .

This is typical of the way that organisations such as the Press Council,

the Advertising Standards Complaints Board, the Broadcasting

Standards Authority, the Human Rights Commission and (indeed!)

the Law Commission treat complaints of discrimination against men.

Such complaints are read down as being

trivial or nonexistent.

The Review makes the point that the Government (i.e. the Attorney-General

and the Minister of Justice) appoints all judges, and that it would

be good if the new regulator was independent of the Government. However,

the Review does not point out that the independence of judges –

once appointed – is protected by the fact that they are well-paid

and appointed for life. The issue is whether a regulator appointed

by the media, together with others, would be more or less independent

than a regular judge. The Review does not make that case convincingly.

Perhaps there is a third way. Perhaps

the regulator could be elected by popular vote. Since I have had many

extremely negative experiences with the Broadcasting

Standards Authority, the Press Council and the Advertising Standards

Complaints Board – to the extent that I consider using their

procedures to be a meaningless ritual that I nowadays engage in rarely

– I am in favour of direct election.

The proposals ignore one fundamental feature of the old media, in

relation to the new media.

It is true that there is a certain "culture of verification"

(Paragraph 4.35) in the old media. However, occasional scandals come

to light, such as that of the Black (i.e. politically correct) New

York Times journalist who regularly made up news stories. I have also

had the experience of having my submission to a Select Committee ignored

by the media, while the submission of another (feminist) group to

the same Select Committee in the same session was turned by the newpaper

concerned into its sole report of the proceedings on that day. It

is impossible to know how common such occurrences are.

The Review is seriously deficient in its analysis. In paragraph

6.56, it states:

The privileges and exemptions conferred on the news media

by law should be conditional on a guarantee that there will be responsibility

and accountability.

Similarly, in paragraph 4.80, the Review states:

... we believe society continues to depend on authoritative

and disinterested sources of information about what is happening

in the world.

Similarly, in paragraph 3.40, the Review refers to:

...the role of a professional body whose primary task is to

provide citizens with accurate and impartial reports on what is

happening in society.

These three statements are complete jokes,

and demonstrates that the Law Commission is either completely hypocritical

or completely out of touch with reality, and that it also does not

understand one of the most important features of the Internet.

There never has been – nor do the Law Commissions proposals

provide – any guarantee that there will be

responsibility and accountability in the new or old media. Indeed,

one of the central themes of my Men's Rights activism since 1987 has

been the lack of responsibility and acountability in the old media.

There is no doubt that society does depend on the old media for news,

but there has never been any credible demonstration that the old media

are authoritative, disinterested, accurate or impartial, as far as

I am aware. Quite the contrary. The Law Commission is essentially

a collection of lawyers, and the Law has one habit which is highly

detrimental in this context: the Law is in the habit of deeming

things to be the case, because it would be impractical to inquire

into the real state of things, in certain circumstances.

I once mounted (and withdrew) a civil court

action against a large number of parties, some of which were media

outlets. In an interlocutory hearing, with the notice "No public

Admittance" (or something to that effect) fixed to the outside

of the door where the hearing took place, a journalist from one of

the defendant newspapers asked the judge for permission to sit in

on the hearing. I objected, but the judge merely described me as "not

liking" the media, said he was not going to have a "closed

hearing", and let her stay. In other words, he was deeming

the media to be the eyes and ears of the people, rather than (in effect)

a totalitarian feminist political party, which is what they are. There

are political parties who also dislike the media, such as the Act

and (to some extent) National parties, but they do not see it as fruitful

or essential to attack the media openly as Winston Peters (New Zealand

First party) does.

It is highly tendentious and offensive to

describe the attitude of people such as Winston Peters and myself

as "not liking" the media. We dislike the media for concrete

reasons, and these reasons are never exposed to proper public view,

because it is the media who control what is exposed to proper public

view. And it is the very facts that the media control what is exposed

to proper public view, and that they use this power for political

(e.g. feminist) purposes that causes us to dislike the media!

The Law Commission itself is a case in point: it is deemed to be

independent. One could say that it is independent of Government, but

is a very empty claim, given that one of its recent Presidents had

previously been a Labour Party Prime Minister, and could easily (if

he had been younger) have become a Labour Party Prime Minister after

being a Law Commissioner, as well! In other words, the Law Commission

has a Left-Wing slant, and its precise relationship to the Government

of the day is almost a detail, in that context.

Similarly, the Review deems the old media to be

authoritative and disinterested, and deems there to be a guarantee

that there will be responsibility and accountability in the old media,

without inquiring into the actual facts of the matter, which prove

the contrary (13indoct.html , ismedia.html

and mediares.html). Although journalists

love to point the finger at how media company owners (e.g. Rupert

Murdoch) allegedly apply political filters to the journalistic process,

it is the journalistic workers at the coal-face who have by far the

greater opportunity to choose what to cover and how to cover it. There

are various degrees of openness about the way that many journalists

see their profession as an opportunity to crusade in favour of certain

values or causes, and there is every reason to believe that this –

both consciously and unconsciously – affects their decisions

about what to cover and how to cover it. There is no journalistic

ethos – let alone any enforced ethos – that promotes "disinterested"

news-gathering and dissemination.

The Review (paragraph 4.83) makes the point that it was the old

media (i.e. The Guardian) which informed us about phone-hacking

by other sections of the media. However, not only was the News

of the World a commercial rival of The Guardian, it

was also (more importantly) an ideological rival. The Leftist Guardian

could probably have dished some dirt on Left-wing papers, but it chose

to attack a Rightist publication. Surprise! Surprise!

I must point out here that even Rightist media seldom cover anti-feminist

news (apart from demonstrations).

I have been on the Internet since before there were any commercial

Internet Service Providers (I used the Wellington City Council's free

service), and the main reason I used the Internet then – which

is still my main reason now – was that it was the only way to

bypass media censorship of pro-men (a.k.a. anti-feminist) views. The

Men's and Fathers' movements – then and now – would have

been totally inconceivable in their present form, if we were/had been

reliant on what the Law Commission's calls "authoritative and

disinterested sources of information about what is happening in the

world". As far as I am concerned, the news media are a criminal,

oppressive autocracy.

In Paragraph 5.6, the Review points out that "Corporatized

media is (sic) a major seat of economic and political power."

That is no doubt true, but the Review does not mention that individual

media workers are also a major seat of political power. After all,

who would tell the Review about that? The media? Of course not, because

they have a conflict of interest. Media workers are quite happy to

tell the public and the Review about their bosses' economic and political

power, but they are obviously not keen to stress their own personal

biases and how they work their way into their day-to-day decisions.

This boss-worker split also hints at the probable role of journalists'

unions in promoting and even enforcing certain Leftist social values,

norms and political agendas (e.g. feminist ones). I found this to

be the case in the Post-Primary Teachers' Association, when I was

a teacher. Whatever the organisation, feminists will work to take

it over, and I am sure that media unions are no different.

I have a Diploma of Journalism and have worked as a journalist,

and I can tell you that the news media are extremely amateurish as

regards what content they publish, which is part of the reason why

they are able to carry out so much anti-male censorship. Their definition

of what counts as news is subjective, ad hoc and arbitrary, at best.

For example, the media seem to follow an unwritten rule, which states:

"Report demonstrations," which is the only reason the Fathers'

Movement has had any news coverage at all.

On the other hand, virtually no pro-male men are asked by the media

to give their opinions on relevant issues, whereas random feminists

are constantly trotted out by the media and called "experts"

for their anti-male views. It must be pointed out that journalists

are often accepted into training courses or jobs for their (Left-wing)

political views, for how well they write (print media), how mellifluous

their voices are (radio) or how physically attractive they are (television),

and that their main academic qualification may be in something as

irrelevant and devoid of logic as English Literature.

Television must be singled out here, as the Review itself does (albeit

briefly). In paragraph 5.13, the Review describes television as having

been perceived "as a powerful, all pervasive medium with a unique

ability to impact on audiences." Watching television requires

little intelligence or concentration, because of its combination of

images and sound, and the frequent use of television for entertainment

corrupts the critical faculties of both the producers and consumers

of television news and current affairs.

Because television "teaches" the same message simultaneously

to vast numbers of people, it creates what are considered to be the

important issues of the day. In other words, the ideological priorities

and other biases and the variable competence of television journalists

become overnight the pressing concerns of a large section of the population,

with obvious political consequences. It is easy to think of Acts of

Parliament that have come into being (directly or indirectly) as a

result of the decisions by journalists (especially television journalists)

as to what kind of event constitutes "news" that should

be placed in front of the public.

The word "teaches" is not inappropriate.

The media are an in-bred little world, in which it is easy for people

to get an inflated sense of their own abilities and importance. The

pretty faces on television, in particular, are bound to attract a

lot of fan mail, and this is bound to go to the recipients' heads,

resulting in a feeling that they have the ability to "make a

(huge) difference" and that they consequently have a duty to

use this power in whatever way they consider to be "wise"

and "responsible", which may incorporate a political agenda.

For example, a TV One newsreader, Judy Bailey, was seriously talked

about as being the "Mother of the Nation", which I found

completely ludicrous – especially as she seemed to use her position

to promote her version of feminism.

Another issue is that the complaints system is based on individual

incidents. The assumption is that media transgressions are rare, and

can be dealt with on a case-by-case basis. However, this system is

inadequate to deal with systemic bias, such as systemic bias against

men. If this bias occurs more or less on a daily basis, there is no

way that a complaints system can deal with it, unless it is deliberately

set up to deal with it.

The Review also does not clearly separate out news from opinion,

advertising, advertorials and entertainment, all of which occur in

the old media. The Review does clearly point out that news is basically

provided only by the old media (i.e. that news-gathering requires

a professional organisation), but it fails to point out that this

is really the only thing that distinguishes the old media from the

new media.

News needs to be treated differently

from opinion, advertising, advertorials and entertainment for the

purposes of regulation. There needs to be some thinking done along

those lines, otherwise the solution chosen for the issue of a regulator

will be inadequate. It is news that society needs. It is news that

is central to what the Review correctly describes as the media's constitutional

function. Opinion, advertising, advertorials and entertainment can

be provided by anyone, and they are only combined with news for practical,

commercial reasons.

The crucial issue is referred to in paragraph 3.43 a.:

The media's functions of providing news to the public, and

ensuring that public officials are held accountable, are so important

in a democracy that the law should not unduly impede their exercise

of those functions.

The Review's ultra-naive approach to the issue of whether the old

media actually do fulfil these functions adequately obscures the fact

that one might just as well state the following conflicting concept:

The media's functions of providing balanced news to the public,

and ensuring that public officials are held accountable in a balanced

fashion, are so important in a democracy that the law should not

unduly impede the thorough supervision of those functions.

As is pointed out in Paragraph 4.27, the old

media's functions are quasi-constitutional in nature. That being the

case, their activities are unacceptably untransparent. What do we

know, for example, about the quantity and nature of the information

that flows into an old media office which constitutes potential "news",

but which is filtered out. What do we know about the overt and covert

criteria which govern what gets filtered out? All this should be in

the public domain, in order for the old media to be accountable.

Here are two examples from the BBC World News programme Foreign

Correspondent, where UK-based foreign correspondents and UK journalists

exchange views in an apparently unscripted conversation: On one occasion,

a female journalist suggested that the truth should be hidden from

the public (I think she was talking about the Euro currency crisis);

on another occasion, an American journalist said that he had hardly

reported the activities of the UK Euro-skeptics, and it could be surmised

from a comment subsequently made by another journalist that he was

"gay", objected to the "homophobic" attitudes

which were assumed to be prevalent amongst Euro-skeptics, and that

this is what had led him to under-report their activities.

PART 2: SPEECH HARMS: THE ADEQUACY OF THE CURRENT LEGAL SANCTIONS

AND REMEDIES

The proposals in Part 2 seem largely appropriate. However, it is

important that the Beyond Reasonable Doubt standard be retained

when putting someone at risk of civil punishment for breaching the

criminal law. Otherwise, they could be acquitted under one standard,

and yet convicted under another, which would tend to lower public

respect for the justice system (and increase calls for the abolition

of the Beyond Reasonable Doubt standard, perhaps).

PERSONNEL ISSUES

It is relevant to speak about the particular individuals who have

been involved with this Review to date – either in the drafting

of it, or because they have been consulted in the course of the drafting

process.

People consulted

-

Twenty-nine people or institutions are mentioned as having contributed

to the drafting of the Review. Twelve of these are old media organisations

(Newspaper Publishers’ Association of New Zealand, The Media

Freedom Committee, The New Zealand Press Council, The Broadcasting

Standards Authority, Fairfax Media

New Zealand, APN News & Media, Television New Zealand) or old

media individuals (Sinead Boucher, Gavin Ellis, Matthew Harman,

Jeremy Rees and Alastair Thompson) or apparently closely linked

to them.

-

Only four people are primarily new media bloggers: Claire Browning,

Fraser Mills, David Farrar and Cameron Slater.

-

The Broadcasting Standards Authority

is outnumbered by four organisations (and at least one of the Review's

authors) which have/have had a stake in the current Press Council

system, which is an alternative model to the Broadcasting Standards

Authority model.

-

Therefore, those consulted included many more of the old media

as opposed to the new media, and many more presumed supporters of

the Press Council model than of the Broadcasting Standards Authority

model.

-

No critics of working journalists are included, as far as I can

see. Naturally, I feel that I should have been consulted, since

I am (as far as I know) New Zealand's most high-profile intellectual

critic of the media, and I am known to the Law Commission. Winston

Peters also criticises the media, but – as far as I know –

he does not do it in any theoretical way. Media studies academics

routinely criticise media owners, but are not known to have ever

investigated Leftist or feminist bias in working journalists, despite

this being an extremely traumatic form of censorship which is suffered

by politically incorrect sections of society on a day-to-day basis.

-

Care Honoré Brett is a former newspaper editor, and therefore

has a conflict of interest. When is she ever likely to draw attention

to the biases of working journalists?

-

Steven Price both taught me Law at Victoria University of Wellington,

and I have a very low opinion of him, from ethical and Men's Rights

points of view.

In short, I consider that there was

significant imbalance in the writing team and in the people consulted.

|